Presentation of the results of the Vincles Alt Pirineu-Aran project for the 2023–2025 period at an event in Sort

Presentation of the results of the Vincles Alt Pirineu-Aran project for the 2023–2025 period at an event in Sort

On 5 March, we held the event in Sort to present the results of the Vincles project for the 2023–2025 period, highlighting both the programme’s success and the need to ensure its continuity.

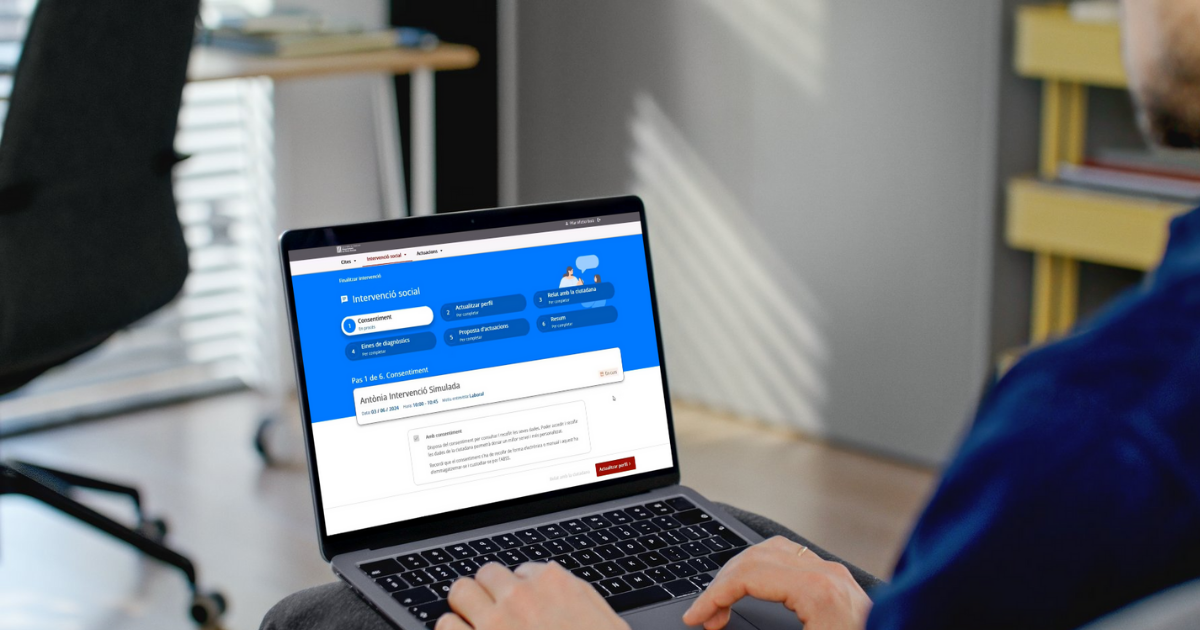

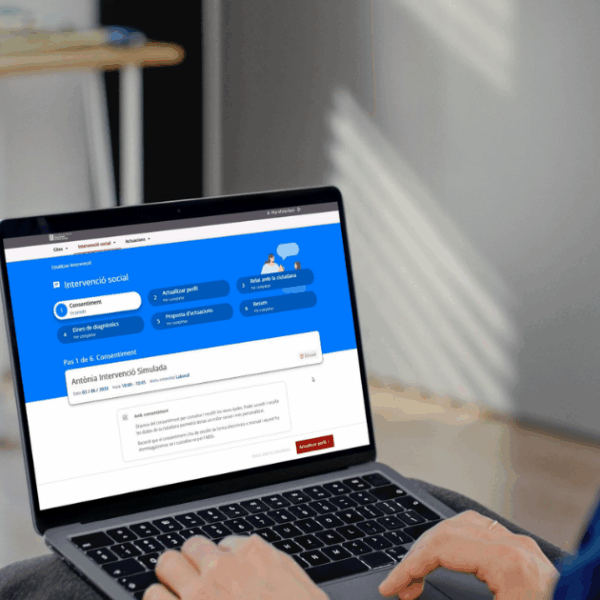

The Consell Comarcal del Pallars Sobirà hosted the event, which showcased the results of the Vincles Alt Pirineu-Aran 2023–2025 project. The initiative, coordinated by the iSocial Foundation in collaboration with the regional social services, proposes a model that combines a technological innovation system for detection—using big data technology—with community‑based intervention actions to prevent and address situations of unwanted loneliness among older people in mountain regions.

The event opened with remarks from Toni Codina, director of the iSocial Foundation; Carles Isús, president of the Consell Comarcal del Pallars Sobirà, one of the territories where Vincles has been implemented; Òscar Martínez, Deputy for Public Health at the Diputació de Lleida; Teresa Llorens, Secretary for Life Cycles and Citizenship of the Government of Catalonia; and Víctor Martínez, Director of Institutions at CaixaBank.

All speakers emphasised the challenges posed by depopulation and the importance of listening to local communities, while highlighting the programme’s success and the need to maintain it.

Later, Marta Ortiz, programme coordinator, presented a real case of an older person experiencing unwanted loneliness, illustrating the challenges faced by social services when addressing loneliness in territories with unique geographical and demographic characteristics.

Alba Palomares, researcher at the University of Lleida, presented the results of the Vincles programme and its impact on the territories where it has been implemented, as well as the methodology used for its evaluation.

The project has been deployed across 30 municipalities comprising 271 population centres in the six counties of the Alt Pirineu and Aran region. The Big Data system, based on 40 indicators, has identified 2,845 people over the age of 55 at risk of loneliness—equivalent to 38% of the population in this age group.

A key component of the project has been the rollout of community intervention actions, with a total of 393 activities involving more than 3,000 participants. In addition, 119 training sessions have been held, engaging and preparing 247 community agents—local residents and professionals involved in detecting situations of loneliness risk. Finally, 205 people have been monitored through 322 follow‑up meetings.

According to the report prepared by the Social Innovation Chair at the University of Lleida, 85% of the people supported report an improvement in emotional and/or social wellbeing; 78% have expanded their social connections within their municipality; 95% would recommend the programme; and 87% express a desire for Vincles Alt Pirineu-Aran to continue.

During the event, Adriana Vidal, director of social services in Pallars Sobirà, highlighted the specific characteristics of the Alt Pirineu and Aran territory, particularly those linked to depopulation. She emphasised the key role of the community activators in the Vincles project, who have worked closely with the Basic Social Services Areas. She also underscored the value of the project’s co‑design process, in which the iSocial Foundation incorporated the perspectives of regional social services from the outset. Finally, she stressed the community‑based and cross‑sectoral nature of the project, which has brought together the six participating territories, public administration, the third sector, and the university.

The event programme included video testimonies and contributions from older participants and volunteers from Vincles Alt Pirineu-Aran, who attended the event and shared how Vincles has become a driving force for community engagement in their municipalities.

Throughout the implementation of Vincles Alt Pirineu-Aran, the use of technology and the cross‑analysis of social and demographic data—combined with community activation—has made it possible to detect and prevent potential situations of unwanted loneliness. Coordination between social services, civil society, and local organisations has created safe spaces and social bonds that foster mutual care and enable faster detection of risk situations. As institutional representatives noted during the event, ensuring the programme’s continuity is essential to continue supporting the needs of the population of Alt Pirineu-Aran.

The Vincles Alt Pirineu-Aran project is led by the iSocial Foundation and the social services of the county councils of Alt Urgell, Pallars Sobirà, Pallars Jussà, Cerdanya, Alta Ribagorça, and the Conselh Generau d’Aran. The project also involves the Social Innovation Chair of the University of Lleida (UdL), IDAPA, the Basque organisations Agintzari and Gislan—developers of the technological tool in the Basque context—and the organisations ABD, Integra Pirineus, and Alba Jussà. It is supported by the Government of Catalonia, the Diputació de Lleida, the “la Caixa” Foundation, and other local partners. During the 2023–2025 period, the project has been implemented with the support of Next Generation EU funds.

Actualitat