The Barcelona Aging coLLaboratory (BALL) aims to create innovative solutions, involving end-users, to improve the quality of life and health and social care of older people. The first project of the BALL, presented today in the Pere Virgili Sanitari Park, is a humanized robot that will help patients who cannot feed themselves, offering them a solution adapted to their needs.

Barcelona, September 26th, 2022.- Aging with the highest quality of life and the best health and social care. This is the main objective of the Barcelona Aging coLLaboratory (BALL), the first Living Lab focused on providing innovative solutions for the elderly that are launched in Catalonia and that has been driven by a wide representation of the estates of civil society.

Today there has been a presentation to the media, in the Pere Virgili Sanitari Park, of the physical headquarters of the DANCE and of its first project: a humanized robot that will help those who cannot feed themselves. This robot is co-creating with end-users, who are instrumental in knowing what they need and thus being able to offer them a solution that fits their characteristics.

In addition to providing patients with a custom tool and greater autonomy, the robot will allow to automate one of the most complex tasks of hospital and residential care logistics, thereby reducing the overload of healthcare personnel, optimising the time and quality of service.

The DANCE, a platform of innovation around aging

The ageing of the Catalan population continues to grow at an accelerated rate and it is estimated that by 2050 one in three people will be over 65. Likewise, according to data from the Institute of Statistics of Catalonia, if the current care model does not change, the dependency rate of the elderly will also increase, from 28.9 % in 2021 to 44.3 % in 2040.

The Living Lab has been driven by ten renowned entities that represent the main areas of Catalan society: Health (Parc Sanitari Pere Virgili and Vall d’Hebron Research Institute), robotics (Institute of Robotics and Industrial Informatics), university (Blanquerna – Universitat Ramon Llull and Universitat Oberta de Catalunya), social (Fundación iSocial), private company (Group Efebé, Qida and UniversalDoctor) and associations of the elderly (Fatec – Federation of Associations of the Great People of Catalonia).

This project operates under the innovation model known as the quadruple helix, where different entities and members of a community (city, business, knowledge centers and administration) join together to build together solutions that are capable of promoting the socio-economic growth of the territory.

“The DANCE is a space or methodology of co-creation involving older people, from the outset, in the design, development, implementation and evaluation of products and services intended to promote their autonomy, integrate them into the community and reduce dependencies and chronicities”, explained by Dr. Marco Inzitari, director of Integrated Atention and Research of the Sanitari Park Pere Virgili and professor of the UOC.

Dr. Inzitari, who is one of the project’s ideologists and promoters, states that “at a time when life expectancy is increasing more and more, but not quality, the ultimate goal of the Living Lab is to put people in the centre and to take control of their health and their life”.

A robot that improves the relational autonomy of patients during meals

The first robot prototype to be presented today has been adapted to software and hardware level to assist people with difficulties in feeding themselves. Designed by professionals from the Institute of Robotics and Industrial Computer Science and the Pere and Virgili Sanitari Park, it has involved all the institutions signed by the Living Lab collaboration agreement. In February, participatory sessions were held with professionals and patients from the Pere Virgili Sanitari Park, where they set out the needs to which they believed the robot should respond to make it more human. His contributions served to build this prototype.

Soon, patients in the Sanitari Park with different difficulties preventing them from eating autonomously will participate in the first pilot test of this humanized robot prototype that is done in a real environment, the hospital, which is where the robot will initially apply.

In this test phase, a group of professionals will conduct interviews with patients to check their degree of satisfaction, as well as closely observe nonverbal reactions during the test. Your responses will be very much taken into account in the final development of the project. Now, the robot is very simple, but in the future, among other functions, it will be able to recognize the patient’s facial gestures and even verbally interact with them.

According to its creators, the robot must contribute to improving the relational autonomy of patients during meals, providing greater choice (in rhythm, type and amount of food), a better image of oneself (increasing self-confidence during eating time), and a larger margin in the dialogic sphere (favoring forms of negotiation about how and what is eaten). Another advantage that the use of the robot will have is that care professionals will be able to obtain much more data concerning the patient’s current nutritional state, which will allow health care to be more personalised, adapting it to each person’s needs and characteristics.

It should also be borne in mind that the administration of meals generates a high-pressure environment because of the burden of dependency on older people, and even more so at such a sensitive time as a result of the increase in the number of people in hospital with a higher degree of dependency and the shortage of professionals in the centres. Our goal with the robot is to be able to dispense more careful and personalized treatment to patients, and reduce the stress of health personnel,” said director of Integrated care and Research at the Pere Virgili Sanitari Park. In addition, it should be borne in mind that the project’s goal is for the robot to be a support rather than a substitute for care personnel, so the robot will never be left alone with the patient.

Josep Carné, president of the Federation of Associations of the Great People of Catalonia, a non-profit entity, made up of volunteers and grouping the associations of the elderly of our country, explains that “although the idea of a robot that feeds the elderly initially pushed us back, we cannot turn our backs on technological advances and more, if they are intended to be a help”. Also, Carné considers that the fact that users play a key role in defining the characteristics that the robot must have is very positive.

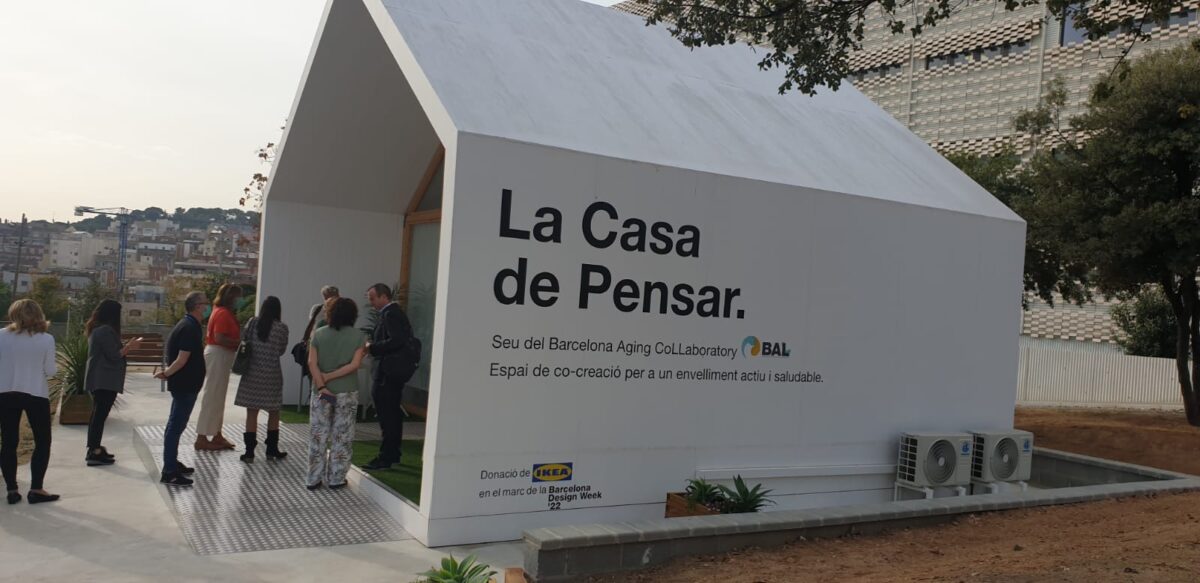

The physical seat of the DANCE: a House of Thought

Living Lab is located in the same area of the Pere Virgili Sanitari Park and is where several participatory dynamics will be performed. Thus, from brainstorming meetings with all ageing-related actors (patient, professionals, research institutions, public administration, private companies, etc.) challenges will be identified in this area. Sessions will also be held to find innovative solutions to these participatory challenges and dynamics in order to develop them with the end

.